Why John Woo's 1980s Hong Kong Action Films Were So Influential

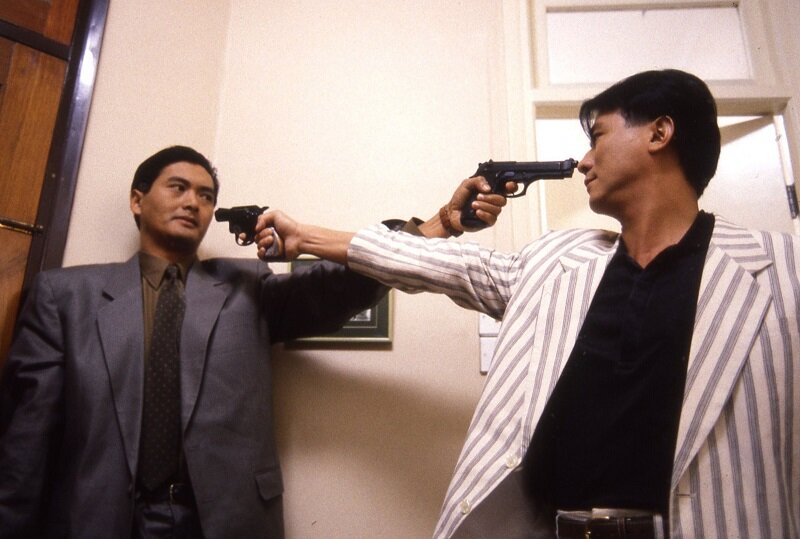

The Killer. Image courtesy of Cinema City.

Hong Kong in the 1980s was in the middle of an explosive economic expansion that began to really take-off in the 1970s. Perhaps coincidentally (but probably not) this was happening at the same time as what is typically considered the Golden Age of Hong Kong’s film industry. During the 1970s and 80s Hong Kong - supported by a domestic population with rapidly increasing purchasing power and eager to spend their disposable income - was the epicenter for some of the best action films of all time.

Hong Kong stars like Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan and Sammo Hung are synonymous with the genre. Golden Harvest, Shaw Brothers and Golden Princess slugged it out in a classic battle of market titans trying to dominate one another (perhaps it was this very competition that helped spur the surge in innovation and output). And in 1986 director John Woo arrived with the release of A Better Tomorrow.

Like Hollywood during its own Golden Age, films in Hong Kong during that time were pumped out at a high volume according to an assembly line process in which star players and directors were often kept under exclusive contract with a particular studio. That was Run Run Shaw’s MO especially. Woo had made a number of these kind of boilerplate films for Shaw before jumping ship to Cinema City for the release of A Better Tomorrow in 1986. It’s commonly accepted now that this film was a watershed, that it birthed a new type of highly stylized action film which influenced a generation of subsequent filmmakers. So what makes A Better Tomorrow so good?

The truth is, if you look at it as a complete film and evaluate its narrative, character development, themes, dialogue and acting - it’s not that good. None of John Woo’s films are what I would call masterpieces in the same way we talk about The Godfather, or 8 1/2, or There Will Be Blood or Blade Runner. Those films are complex, beautifully acted and they explore interesting aspects of the human condition or psyche. Like Sons of Anarchy, A Better Tomorrow is perhaps best viewed as Greek tragedy. The themes and ideas it plays with are big and bold and sweeping and epic - loyalty, love, revenge, honor. There are also ridiculous little bits, like a cello audition gone wrong, jammed in among all the operatic flourishes.

But, in my opinion as a viewer, it doesn’t come together to make a good, complete film. What A Better Tomorrow excels at is creating a series of disconnected experiential moments, augmented with extraordinary style that are then stitched together by pretty bad plotting and overwrought characterizations and dialogue and acting (with one obvious and important exception).

The highly stylized experience of A Better Tomorrow was John Woo’s primary innovation with this film - the use of freeze frames, of slow motion, of music and costumes to create these sensuous moments in time that seem to flow off the screen and into the air. The most iconic is the nightclub shootout, which is just a beautiful moment in cinema. But the opening sequence in which we meet Mark and Ho is also overflowing with style as it establishes the singular look and feel of the film.

It also introduces us to Chow Yun-fat, who before this movie was not much of a star in the Hong Kong movie scene. But right from the word go, he oozes movie star charisma and screen presence as Mark, the loyal avenging angel of death who will come to dominate the film. This role catapulted Chow to stardom, and he’s very good, conveying Mark’s razor edge intensity as well as his good nature and strong crook morality through little gestures and tics, like the way he’s always doing some weird business with or around his mouth. Little mannerisms like that are what sell a truly good performance, rather than the big dramatic moments where most actors just chew scenery.

Which is ironic, because Chow’s nuanced performance is the backbone of a film that is almost entirely, from start to finish, loaded with big, loud scenery chewing spectacle. Don’t get me wrong, many of the action scenes look great. And the way Woo controls the visual space of his films is masterful and hypnotic, with hyper kinetic camerawork mashed up with freeze frames, slowing down and ramping up the speed of time and motion in a way that seems like it wouldn’t work, but somehow does. It has been described as poetic or balletic, and that’s pretty apt.

It’s visually brilliant, and moody and stylish and not subtle. Which serves perhaps as a good complement to these broad, somewhat silly themes in the movie about brotherhood and love and duty and honor. But you will never convince me that the non-action scenes in this movie are “good” filmmaking, and even the action sequences, like the final shootout, start to get really silly after a while. John Woo, it must be said, never met an explosion he didn’t love. Nevertheless, the film introduced an interesting visual aesthetic and it was a monster hit in Hong Kong.

The Killer is the natural successor to A Better Tomorrow, and it fits the exact same template but perhaps with a bit more confidence this time. Chow Yun-fat plays a charismatic assassin with a heart of gold who gets wrapped up in a game of cat and mouse with his police officer foil, played by Danny Lee. As in A Better Tomorrow, stylish action sequences are inter-cut with quieter moments in which the movie’s obsession with big broad themes of honor, duty and underworld morality are allowed to breathe. It is very clearly a precursor to Michael Mann’s Heat, although far less terrible. Nobody can shoot two people pointing guns at each other with such madman energy as John Woo, and the coolness of the film during certain moments just flies off the screen.

But it also suffers from the same hang-ups as A Better Tomorrow - hammy acting, overwrought dramatic moments, bad plotting (if you were a lounge singer and a man blinded you in a shootout, of course it’s only natural that he then becomes your savior and you his redemption). John Woo has never been able to escape his own gravity - he has such an amazing control over the style and the visual aesthetic of his films, to a degree where you can almost feel them as a tactile experience as you watch.

But all the other elements that are typically necessary to make a good film - the acting, the plot, the dialogue, the themes - are just window dressing and after thoughts. Hard Target embodies this quite thoroughly and as I will discuss in my next post, I think this is why Woo’s style worked well in Hong Kong but struggled to really catch on when he made the jump to Hollywood. It’s all flash and no sizzle, and the heroic themes that played so well for Hong Kong viewers didn’t have quite the same snap in America.

The other really interesting thing about Woo’s Hong Kong action films is that they occupy a crucial fulcrum in the DNA of cinema history. Woo’s films are heavily influenced by French, Japanese, American and even Hong Kong films that came before. He has credited Martin Scorsese and in particular Mean Streets, as well as Le Samourai, as being big influences on his Hong Kong actioners. But when I watched A Better Tomorrow the first thing that came to mind was Sam Peckinpah and The Wild Bunch. The Wild Bunch glorified violence with the same kind of reverential stylization, speeding up and slowing down time for dramatic purposes and hitting on similar themes of outlaw morality and honor. Arthur Penn’s fingerprints are similarly visible in Woo’s work.

Woo took those stylistic and thematic influences from the revisionist Westerns of the late 1960s and he reinterpreted them, gave them a Hong Kong twist and a sultry dream-like quality steeped in operatic violence and squib orgies. In a way, his films from the 1980s act as a prism, refracting the work of Peckinpah, Penn, Scorsese and Jean-Pierre Melville through the lens of Hong Kong’s booming film industry and projecting it into the 1990s where it reformed into the work of Michael Mann, Tarantino and the Wachowskis - to name just some of the most obvious and famous.

Fundamentally, I do not think John Woo’s Hong Kong films are great movies. I think they are singular experiences, with moments of truly visionary spectacle carried along by the revelatory performance of an actor discovering he is a movie star. But the bones of truly good cinema are largely absent. Nevertheless, these films have been amazingly influential on later generations of filmmakers, who have tried to incorporate the visual wizardly, the style, the moodiness and the effortless sense of cool into their own visions of epic crime sagas. And to watch a John Woo film is in many ways like enjoying a piece of abstract art - you can marvel at the intensity of the thing before you, without thinking it is as fine or precise a piece of art as a Rembrandt. And ultimately, I think that may be what held his films back in the US market.

That and John Travolta.